Pair foster families with biological families in a mentoring program

By Georgia Mjartan

* This article was Published in the Arkansas Times Big Ideas for Arkansas 2015 Edition. To read other big ideas click here

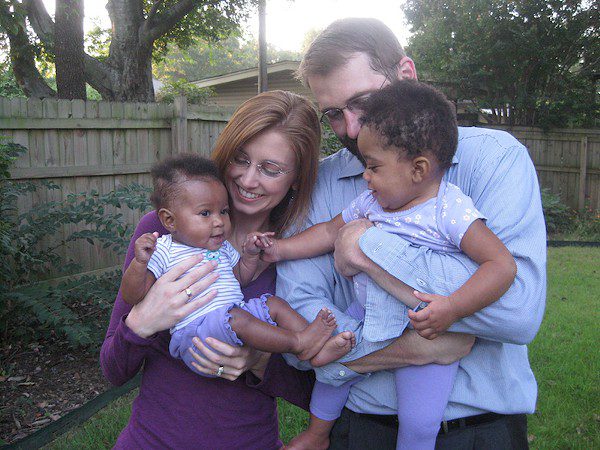

Foster families are sometimes referred to as resource families, since our job as foster parents is to be a resource to the child or children in our care. But what if we could be a resource not only to the children, but also to their biological parents?

Long-term foster care tends to be a painful and confusing experience for children. The goal is always to find a permanent situation, whether children are returned to their biological families or adopted into a new home. As foster parents, the question guiding all of our decisions should be, “How can I make this child’s life better?” One way to do this, when appropriate, would be to mentor the child’s biological family.

At present, involvement between foster parents and a child’s biological family is often discouraged. When a person decides to foster or adopt through the state Division of Child and Family Services, they are given a choice of three check boxes on a form: foster care, adoption or provisional foster care (an option for family members seeking to foster a relative). There used to be a fourth option, foster-to-adopt. That choice was removed, I understand, because of concerns that foster parents hoping to adopt the children in their care were working against the goal of reunification with the biological family. I envision a wider selection of choices for engagement, including the option to be a foster-mentor family. Everyone — DCFS caseworkers, foster parents, biological parents and, most importantly, children — would benefit from a greater breadth of options available for the complex and life-changing relationships that this system brokers.

At first, foster-mentor families would look just like regular foster parents. A child or children in need of care would be placed in their home. But as the case progressed, if caseworkers, ad litem attorneys and judges deemed the biological family to be good candidates, the foster parents would be asked if they would be willing to also serve as mentors to the biological family members trying to reunify with their children. Foster families would mentor through both words and actions —modeling better, healthier child-raising strategies for biological parents.

As executive director of Our House, I have been inspired by the life-changing power of positive, mentoring relationships. I have seen complete transformations occur in the lives of people whom society has written off. I have seen people with histories of addiction, crime and homelessness become clean, stay sober, get jobs, save money and provide for themselves and their children. Accountability is key, and DCFS currently provides that: Biological parents often are required to submit to drug tests, attend mental health counseling and take parenting classes as part of the mandated plan to get their children out of foster care. We provide these kinds of services at Our House, too, and I know their value firsthand. But I am also convinced that rules and brokered services are not enough.

I can only imagine the tremendous worry that a parent feels when his child is taken from him. What a powerful and grace-giving experience it must be for that same parent to receive love, kindness, encouragement and practical support from the same people who are serving as the temporary parents to their children. If we had a formal foster-mentoring program, maybe we could take a situation that is painful for everyone and make it a little better. We could use the resources of foster parents to help biological families become better equipped to raise their children. Most importantly, we could show the children in our care that our love for them extends to their biological families as well, thus helping to integrate and lessen the pain of a disjointed childhood.

Georgia Mjartan is the executive director of Our House.